What are the Dietary Guidelines, and why do they matter?

anaumenko - stock.adobe.com.

If someone asked you what you’ve heard about the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, would you know what to say? You’ve probably heard of the Food Guide Pyramid (which hasn’t been used in about 15 years), and you might have recently heard something about the Guidelines being the cause of America’s health woes (not true). We’re here to set the record straight.

What are the Dietary Guidelines for Americans?

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA) are recommendations for how we should be eating to meet nutrient needs, promote health, and prevent chronic disease. The Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Health and Human Services (HHS) are responsible for updating the Guidelines every five years, incorporating the latest available science on nutrition (more on that below). This is required by law: the National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act of 1990 mandates that the Secretaries of USDA and HHS publish the Guidelines at least once every five years and that they be based on scientific evidence.

How are these guidelines used?

Although the Guidelines are written primarily for an audience of policymakers and healthcare providers, they inform public-facing recommendations like MyPlate, a simple visual that distills the scientific research into a reminder to choose a variety of foods at each meal while filling half of your plate with fruits and vegetables and the remainder with grains (preferably whole) and protein.

Don’t use MyPlate or refer to the Guidelines for your dietary decision-making? That doesn’t mean the Guidelines haven’t influenced your—or your neighbor’s—diet.

The Guidelines play a role in many people’s lives because they form the backbone of national nutrition policies and shape what foods can be served or purchased in many programs, including the National School Lunch Program, the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), and the nutrition education offered with the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). In fact, at least 16 nutrition assistance programs that are informed by the Guidelines together serve 1 in 4 people in the United States every year. That includes the 30+ million kids who eat school meals, which must meet the nutritional standards created especially for school meals based on the Guidelines.

Finally, the Guidelines are also often used by healthcare professionals and community health workers to promote healthy eating for their patients and clients.

Wait, what happened to the Food Pyramid?

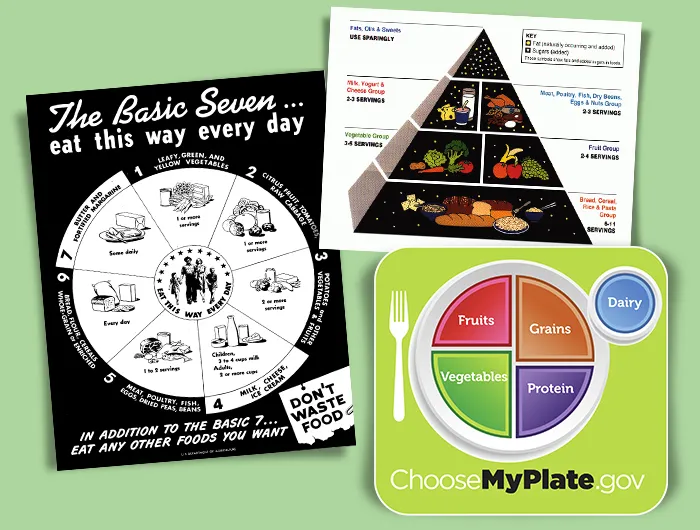

Ah yes, the Food Pyramid! For a while there, you couldn’t escape it. It was on the back of cereal boxes, all over classrooms, and maybe even on the waiting room wall at your doctor’s office. You might be surprised to hear that the Food Pyramid is out of date and hasn’t been in official use since 2011, when it was replaced by MyPlate.

One of the issues with the Food Pyramid was the very top of the pyramid: That’s where you could find all sweets, fats, and oils (without differentiating between the kinds of fats and oils). Placing those in the smallest part of the graphic was intended to communicate that we should consume those items in small amounts. In 2010, the Guidelines got a little more specific on this point and pushed consumers to replace saturated fats, like butter, beef tallow, and lard, with healthier monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, like those found in salmon, peanuts, and olive oil. But the structure of the Food Pyramid—and its lumping all fats and oils together—didn't allow for a visual representation with the necessary nuance.

What’s more, the Food Pyramid isn’t a useful guide for many, as most people don’t keep tabs on what they’ve eaten throughout the day, or adjust their meals along the way to ensure they’re hitting their serving goals.

A big benefit of MyPlate is that the simple graphic reminds people to pile on the fruits and veggies. Instead of thinking in terms of servings—and really, how many people know what a serving of pasta actually looks like?—as the Food Pyramid prompted us, we can instead remember that fruits and vegetables should take up half of our plate. In general, MyPlate is more intuitive to use for a lot of people.

How else have the Guidelines changed over time?

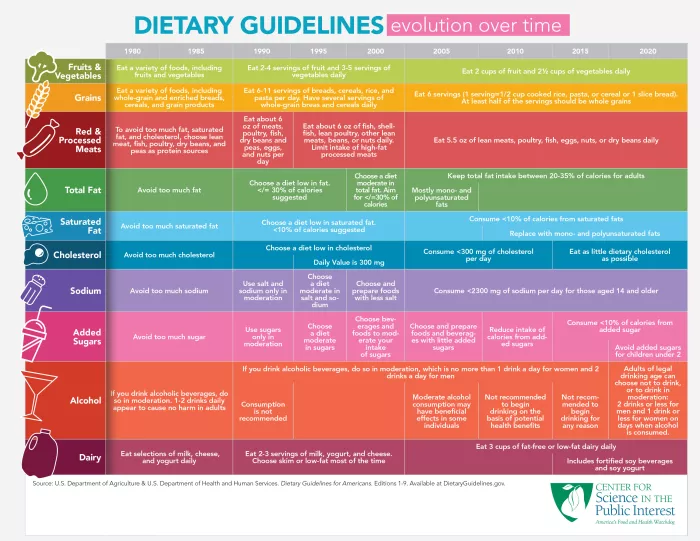

Since they were first published in 1980, the Guidelines’ advice for healthy eating has stayed remarkably consistent. There have been no large departures from former Guidelines, nor have they flip-flopped. Instead, most of the changes are due to increasing specificity, often in ways that reflect the evolving science. (That’s not because the scientists haven’t been diligent in reviewing the evidence. It’s because they have understood the foundational ideas for a while and, so far, only refining the concepts has been warranted.)

As mentioned, the guidance has sometimes evolved to be more specific. In 1980, the Guidelines recommended that people “avoid too much sodium.” In 2005, that recommendation shifted to “Consume less than 2,300 milligrams (approximately 1 tsp of salt) of sodium per day.” Recommendations for added sugar changed from a general message about avoiding too much in 1980 to a much more specific guideline to consume less than 10 percent of calories from added sugars in 2015. In 2020, the Guidelines added that children under the age of two should avoid added sugars altogether.

At times, the Guidelines have also changed because the science has changed. One important example is related to dietary fat. The 1990 version of the Guidelines suggested that people aim to get no more than 30 percent of their calories from fats, and specifically to limit saturated and trans fats. (Fortunately, artificial trans fats were removed from the US food supply in 2018.) In 2005, the Guidelines bumped up the limit on total fat intake to 35 percent of total calories. That’s because new research showed that diets that included up to 35 percent of calories from fat could still be healthy—that is, consuming that amount of fat is not linked to cardiovascular disease or various types of cancer. But the type of fat matters. Instead of focusing on total fat, the recommendations shifted to underscore the importance of limiting saturated fat. Although the Guidelines had always encouraged limiting saturated fat, they recommended a specific quantitative limit in 2005 for the first time: Saturated fats should take up no more than 10 percent of your total daily calories, and trans fats should be limited as much as possible. Those recommendations remain today and inform policies and programs like school meals.

The DGA and health

If the Guidelines inform school lunches, why are they full of junk?

The food served to kids in school might call to mind your days eating square pizza in the cafeteria, but school lunches are a lot healthier than they used to be. School meals must meet age-appropriate limits on calories, sodium, and saturated fat, and limits on added sugars are currently being phased in. Schools are also required to offer fruits and vegetables daily, and a variety of vegetables must be offered over the course of the week. Lastly, school lunch programs also must ensure that at least 80 percent of the weekly grains being served in meals are whole grain-rich, working toward the recommendation in the Guidelines that at least half of total grains should be whole grains. So even though pizza and chicken nuggets are still on the menu, that pizza is likely made with at least some whole grains, less sodium, and low-fat cheese, and the chicken nuggets are likely breaded in whole–grain–rich breading. Both are served with fruits, vegetables, and low-fat or non-fat milk.

All these recommendations add up to some important results for children. Research shows that school meals are the healthiest food that kids eat. The changes in school lunches have resulted in improvements in the nutritional quality of food consumed by kids, regardless of their age, sex, race or ethnicity, parental education level, or household income. That type of equitable outcome is all too rare in public health.

Have the Dietary Guidelines caused the United States’ health problems?

No. For starters, many Americans don’t follow the DGA’s advice, and we never really have. That’s not because people don’t want to. Rather, our food environment—with cheap, tasty, calorie-dense food available around the clock, on every corner, and in every check-out line—doesn’t make healthy choices easy.

As Marion Nestle, Professor Emerita of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University put it, “Ultraprocessed junk foods are among the most profitable for the companies that make them, and the companies’ first priority is profits for stockholders. To sell those foods, companies bombard us with billions of dollars in ads, normalize eating junk food, and make it available 24/7, everywhere, and in large amounts at remarkably low cost.”

Maybe you’ve heard something about unhealthy weight gain skyrocketing just when the Guidelines first came out in 1980. It’s reasonable to ask whether there’s a link between those two changes because they seem to have happened around the same time.

The theory was based on the claim that when the DGA first urged us to eat less fat in 1980, people swapped fat-rich foods for sugary ones. (In reality, the DGA warned us against overconsumption of both fat and added sugars, a point not often made by people blaming the low-fat guidance of the 1980s for our health woes.) But data collected between 1976 and 1994 indicate that Americans’ dietary fat intake dropped only slightly, from about 36.4 percent of total calories to about 34 percent over that time.

What else happened to our diets? Put simply: We started eating more food. Between 1975 and 1994, the average US adult ate roughly 260 more calories per day. So the climbing number of people with excess weight can’t be pinned on the first edition of the Guidelines, but rather on the fact that food became more available (thanks to the food industry) and we ate more of it.

Unfortunately, diets in the US have never reflected the guidance of the DGA. For example, we all know we should be watching our salt and sugar intake, partly because the DGA have been telling us to avoid an excess of both since 1980. But 89 percent of people over the age of 1 consume more sodium than recommended, and 65 percent consume too much added sugar. For decades, the DGA have advised us to limit our consumption of saturated fats, but 82 percent of us consume more than the recommended amount. And despite the DGA’s guidance on fiber, 94 percent of us aren’t consuming enough of it.

Since 1995, we have also had a measure of overall alignment of the average American diet with the guidance of the DGA: the Healthy Eating Index (HEI). The HEI is a 0-100 measurement where a higher score indicates a diet more aligned with the Guidelines. Our HEI scores have been consistently low: In 2020, Americans over the age of 2 scored just 58 out of 100 on the HEI on average, driven down in particular by our inadequate consumption of whole grains and healthy fats and high consumption of sodium and saturated fat.

Because so few of us are actually following the DGA’s advice, it just doesn’t make sense to place the blame for our issues with cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and other chronic health problems on them. Rather, the focus should shift squarely to how the food industry has flooded our environment with fries, cheeseburgers, pizza, burritos, chips, soda, candy, and so, so much more.

How can following the Guidelines help prevent chronic disease?

It’s clear that, as a country, we’re not doing a great job of following the Guidelines. But there is strong evidence that we would be healthier if more of us were able to follow them.

A 2024 analysis of studies that included data from more than one million participants concluded that those whose diets scored higher on the HEI had a lower risk of early death overall and from either cancer or cardiovascular disease. Another study found that a higher score on the HEI is also linked with a lower risk of developing diabetes.

The 2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

During every cycle of revising the Dietary Guidelines, a committee of scientists known as the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee first evaluates all the evidence in question and writes what’s called the Scientific Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee. That report then goes to USDA and HHS to help the agencies write the new Guidelines. Interested in learning more about that process? We’ve laid it all out for you.

Are there important changes in recommendations in the latest report?

There are no earth-shattering changes recommended in the 2025 Scientific Report. But there are some interesting shifts to be aware of.

The Advisory Committee has suggested a new framework for thinking about healthy eating, an inclusive and flexible plan called Eat Healthy Your Way. The new framework emphasizes plant-based proteins like beans, peas, and lentils rather than red and processed meat. Eating a plant-rich diet is great for your health, and the Committee specifically noted the cardiovascular benefits of replacing a diet high in saturated fat from red meat and dairy products with a diet featuring a variety of plant-based foods. Previous versions of the Dietary Guidelines listed beans, peas, and lentils as a subcategory of the vegetable food group. The new recommendation is to include them in the protein food group in order to align with recommendations to emphasize plant-based proteins.

What’s more, the Report recommends reorganizing the protein food group so that beans, peas, and lentils are center stage, followed by nuts, seeds, and soy (like tofu or tempeh), then seafood, and finally meat, poultry, and eggs. This new emphasis on plant-based proteins could help shift the way people think about what foods count as protein. For example, not many people realize that a serving of soy milk has as much protein as a serving of dairy milk. Or that you can get nearly as much protein in a serving of tempeh as you can from chicken thighs. And down the road, the reorganization of the protein group could have a positive impact on the types of foods included—and meals served—in programs like WIC and the National School Lunch Program.

Learn more: How to find the best plant milk

The Advisory Committee also recommended that USDA and HHS form a panel of experts to figure out why most of us don’t follow the Guidelines. They recommend that these experts in health behavior and communication should be tasked with identifying research-based strategies to improve diet quality. Those results could lead to important policy changes that may help improve how we eat.

What did the Committee say about ultra-processed foods?

Ultra-processed foods include industrially manufactured products like carbonated soft drinks, energy drinks, candy, hot dogs, lunch meat, cakes, and cookies. But foods like whole wheat bread, soy milk, and flavored yogurt also fall into this category.

The Committee addressed ultra-processed foods by conducting a systematic review on the following question: “What is the relationship between consumption of dietary patterns with varying amounts of ultra-processed foods and growth, body composition, and risk of obesity?”

For this systematic review, the Committee identified peer-reviewed studies published between 2000 and 2024, looking for high-quality evidence of the effects of ultra-processed foods on health. They found just 48 studies. Committee members noted limitations about both the quantity and quality of the studies they found, because all but one of them were observational studies rather than randomized controlled trials, making it hard to draw any solid conclusions about the relationship to weight outcomes. Their findings echo more general concerns about how hard it can be to study the link between ultra-processed foods and health. In particular, maybe people who consume more ultra-processed foods have other poor health habits like smoking, drinking alcohol, or lack of exercise. Or it could be that rather than the processing procedure, some of the ingredients in many ultra-processed foods, like excess salt and added sugars, are actually the problem.

Because of those limitations, the Committee concluded that the findings amounted to “limited” evidence (the second-lowest of four tiers of evidence) that diets high in ultra-processed foods are linked to excess body weight in children, adolescents, and adults. Because of this limited evidence, they decided that they couldn’t make a recommendation for or against limiting ultra-processed foods, instead calling for more research on the topic.

But don’t take that conclusion as a suggestion that the Guidelines don’t recommend limiting most ultra-processed foods. In effect, the 2020-2025 edition already promotes diets low in ultra-processed foods by highlighting the importance of eating nutrient-dense foods, limiting our intake of saturated fat, added sugars, sodium, processed meats, and sugar-sweetened beverages, and increasing our intake of whole grains. Not many ultra-processed foods qualify once you’ve made those adjustments.

Do corporate interests ever influence the Dietary Guidelines?

Yes. Industry groups and lobbyists (as well as members of the public) can provide comments while the Advisory Committee is writing the Scientific Report. But historically, their real influence has come into play when USDA and HHS are writing the Guidelines. The work is quite public-facing and transparent until that moment, when the entire process moves behind closed doors.

For example, in 2015, the Committee suggested that food system sustainability should be considered in the Guidelines for the first time. The scientists pointed out that more people choosing diets higher in plant-based foods and lower in meat and dairy products would contribute to food security for future generations by curbing climate change. But when the final version of the Dietary Guidelines came out, HHS and USDA officials didn’t include any mention of sustainability, and there was no information about the connection between diet and climate change.

Why the omission? Perhaps because encouraging people to eat fewer animal-based foods threatens the meat industry’s bottom line.

Writing about the decision in the journal Science, a team of experts explained: “The meat industry feels especially under attack. Much discussion of sustainable diets has focused on the increase in livestock production that will result from population growth and adoption of Western-style diets by an expanding middle class in the developing world. Whether from a health perspective (e.g., reducing coronary heart disease) or an environmental perspective (e.g., reducing methane emissions and deforestation) the dietary advice is the same: eat less meat.”

What’s more, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, a lobbying group that works to influence policy on behalf of beef producers, submitted comments on the 2020 Guidelines espousing the benefits of beef in a balanced diet and pushed the government to keep beef in the final recommendations. In the end, it seems like the $303,000 they spent lobbying between 2014 and 2016 to keep beef in the guidelines worked out to be a pretty good investment for them... and a pretty bad deal for our health.

Five years later, HHS and USDA also ignored the Committee’s suggestion that the guidelines on alcohol consumption be modified to advise that people who do drink alcohol should drink no more than a single serving of beer, wine, or liquor a day instead of up to two a day for men and one a day for women. The American Institute for Cancer Research criticized the decision as evidence that the agencies had “bowed to industry pressure” on alcohol.

Will industry influence the 2025-2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans? Or will the heads of HHS and USDA, Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. and Brooke Rollins, resist the food industry’s lobbying efforts, which they've long criticized? As their approval is necessary for the Guidelines to be released to the public, the ball is squarely in their court.

Key takeaways

- Science is always evolving. We are continuously getting better at figuring out what will keep us healthy. That’s a normal part of the scientific process. As high-quality science evolves, policy should follow suit.

- For good reasons, the Guidelines have remained pretty consistent over the years. We have known for decades that a diet high in fruits, vegetables, legumes (like beans and lentils), nuts, whole grains, seafood, and lean meat is better for us than a diet high in red and processed meat, refined grains, saturated fat, sodium, and added sugar. The challenge now is to get people to more faithfully follow that advice.

CSPI is your food & health watchdog

We envision thriving communities supported by equitable, sustainable, and science-based solutions advancing nutrition, food safety, and health.

As a nonprofit organization that takes no donations from industry or government, CSPI relies on the support of donors to continue our work in securing a safe, nutritious, and transparent food system. Every donation—no matter how small—helps CSPI continue improving food access, removing harmful additives, strengthening food safety, conducting and reviewing research, and reforming food labeling.

Please support CSPI today, and consider contributing monthly. Thank you.

More on the dietary guidlines

Health and science professionals question scientific basis of 2025–2030 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

Government Accountability

What changed in the new Dietary Guidelines & why it matters

Healthy Eating

Is saturated fat good or bad?

Healthy Eating

New Dietary Guidelines undercut science and sow confusion

Government Accountability

5 things we want to see in the 2025 Dietary Guidelines

Healthy Eating