Climate change is worsening. Our children will pay the price

Michal - stock.adobe.com.

The government can urge industry to “drill, baby, drill,” vow to end “the green new scam,” and erase rules to limit greenhouse gases. But that won’t erase what may be irreversible damage to the planet our children inherit. Here’s the latest on climate change...and how your diet can matter.

1. Last year was the hottest ever...again.

“2024 was the warmest year on record,” announced Russell Vose, chief of the Monitoring and Assessment Branch at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), at a press conference in January.

In 2024, the average global temperature topped the pre-industrial (1850–1900) average by 1.46° Celsius (2.63° Fahrenheit), according to NOAA.

El Niño—the periodic warming of the Pacific Ocean—was partially to blame.

Another contributor: “Shipping regulations implemented in 2020 reduced the emission of sulfur dioxide,” noted Vose.

Sulfur dioxide can worsen problems like asthma and bronchitis by irritating and inflaming airways. But cutting sulfur dioxide has a downside.

“If you have reduced emissions, that implies fewer clouds and more sunlight reaching the Earth, heating the ocean, and warming,” said Vose.

What’s more, “polar sea ice has been at very low levels. That allows more energy to hit the ocean rather than being reflected back to space.”

But the main driver is no surprise.

“Of course, there’s been concentrations of gases like carbon dioxide, which is 50 percent higher than pre-industrial levels,” said Vose. “Methane and nitrous oxide are also up about 150 percent and 25 percent.”

And those greenhouse gas emissions have taken a toll.

“It’s very, very clear that the heat waves that we’re seeing would not have been happening without anthropogenic climate change,” said Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, at the press conference. (He was referring to changes caused by human activity.)

“The intense rainfall increases that we’re seeing almost everywhere would not have been happening without anthropogenic climate change,” added Schmidt.

Heat waves, heavy rainfalls, and wildfires are all signals of that climate change, he explained.

“The signal now is so large that you’re not only seeing it in the global mean, you’re not only seeing it at the continental scale, you’re not only seeing it at the regional scale,” noted Schmidt. “You’re seeing it at the local scale. You’re seeing it in local weather.”

NOAA’s reported 1.46° C rise in global temperature was less than those reported by the UK’s Met Office Hadley Centre, the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, and Berkeley Earth.

“Using an average of multiple data sets, 2024 was about 1.55° Celsius above the average for 1850 to 1900,” said Vose.

However, topping 1.5° C in 2024, noted Schmidt, “doesn’t mean that we’ve exceeded it in the context of the Paris accord, which is over a longer time period.” (He was referring to the 2015 Paris Agreement, which set a 1.5° C limit of warming to avoid the most devastating climate disasters.)

But that’s not much comfort.

“We anticipate future global warming as long as we are emitting greenhouse gases,” said Schmidt.

“Until we get to net zero, we will not get a leveling off of global mean temperature...and that’s something that brings us no joy to tell people.”

2. The Arctic is no longer a carbon sink.

In December, NOAA released its 2024 Arctic Report Card. The news wasn’t reassuring.

“The Arctic continues to warm more quickly than the globe overall,” Twila Moon, deputy lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado, told the press.

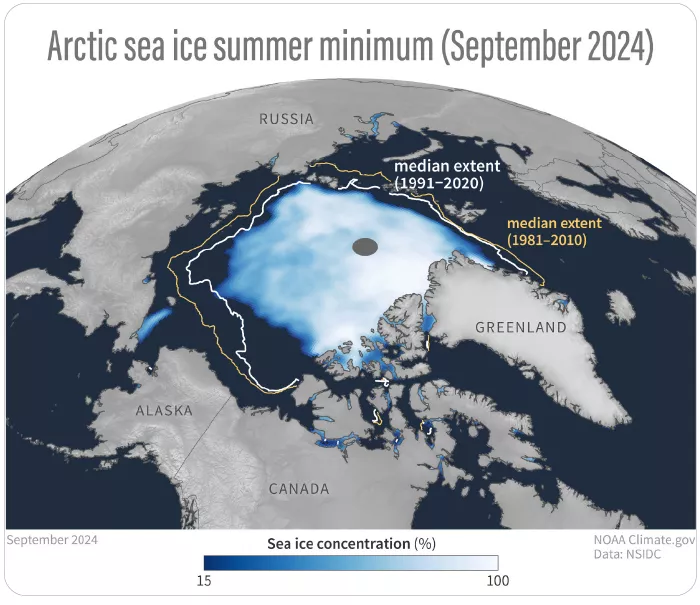

That warming has taken a toll. The Arctic’s summer sea ice extent “is only about 50 percent of what it was in the 1980s,” noted Moon.

And a warmer Arctic means trouble.

“The region contains massive amounts of carbon in its soils, most of that locked up in permafrost, ground that has been frozen for hundreds to thousands of years,” explained Brendan Rogers, associate scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center in Falmouth, Massachusetts.

“The Arctic has acted as a carbon sink for millennia, gradually building up these large terrestrial carbon stores as plants photosynthesize, taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and depositing carbon into the soil, where microbial decomposition has historically been slow because of cold temperatures and frozen soils.”

But the permafrost is no longer permanent.

“As climate change is happening, soils warm, permafrost is thawing, and microbes are waking up,” Rogers pointed out. “And that decomposition—[causing] emissions of carbon dioxide and methane back into the atmosphere—is increasing.”

What’s more, Arctic wildfires have become more intense.

“Wildfires combust vegetation and soil organic matter, emitting that carbon back into the atmosphere,” said Rogers. “And by removing insulating soil, they can also lead to longer-term permafrost thaw and carbon emissions.”

The result: “The permafrost region, which historically has acted as a carbon dioxide sink, has been essentially carbon dioxide neutral over the past 20 years,” noted Rogers.

Translation: The Arctic is no longer helping to cool the Earth.

And the Arctic tundra—a large expanse of treeless lands in the far north—has shifted from a sink to a source of carbon dioxide.

“This transition from a carbon sink to a source is of global concern because carbon dioxide and methane are heat-trapping greenhouse gases,” Rogers explained.

3. Earth is warming faster than expected.

“We Earth-system scientists and climate scientists are getting seriously nervous,” said Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and professor of Earth-system science at the University of Potsdam, in a 2024 TED Talk.

“We are, despite years of raising the alarm, now seeing that the planet is actually in a situation where we underestimated risks.”

From 1970 to 2010, the world’s average temperature climbed by 0.18° C per decade, said Rockström. But in the decade starting in 2014, it rose by 0.26° C.

“If we follow this path, we will crash through 2º Celsius within 20 years and hit 3º Celsius by the year 2100, a disastrous outcome, caused by us humans,” he warned.

Why is the planet heating faster than expected? For starters, its buffering capacity may be dwindling.

“So far, Mother Earth has been so forgiving,” said Rockström. “Fifty-three percent of the carbon dioxide from fossil fuel burning and land system change has been soaked up by intact nature on land and in the ocean.”

But forests in Canada, Russia, Germany, and elsewhere may be losing their capacity to absorb carbon.

“Did you know that the latest science shows that part of the Amazon rainforest, planet Earth’s richest biome on terrestrial land, has already tipped over and is no longer a carbon sink?” asked Rockström.

“It is today a carbon source. It’s no longer helping us.”

The oceans worry him even more.

“The ocean absorbs 90 percent of the heat caused by human-induced climate change,” he noted.

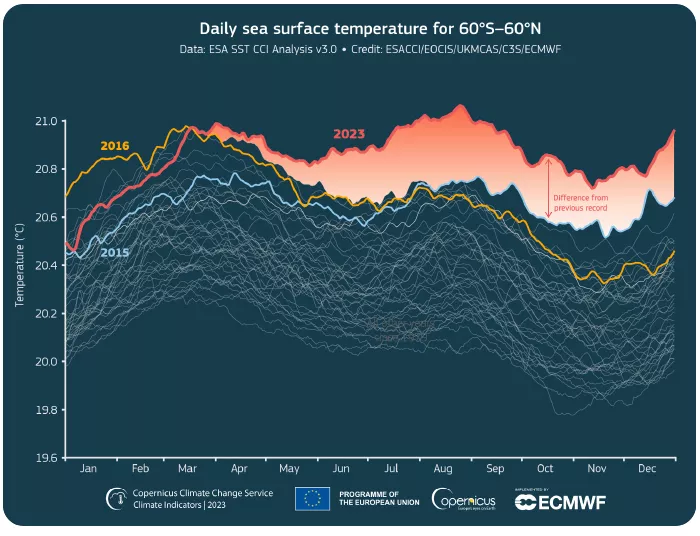

Since 1980, the oceans have gradually gotten warmer and warmer.

“Then suddenly in 2023, something happens,” said Rockström. “Temperatures just go completely off the charts, 0.4º Celsius outside of the warmest temperature in previous years.”

It’s not clear why.

“Is it...an ocean that is starting to lose resilience?” Rockström asked. “An ocean that is at risk of releasing heat to the atmosphere and self-amplifying warming? We do not know. But one thing is for certain: The ocean is sounding the alarm.”

The oceans aren’t the only Earth system that could tip from friend to foe.

“Big systems like the Greenland ice sheet, the overturning of heat in the North Atlantic, the coral reef systems, the Amazon rainforest are tipping element systems,” explained Rockström.

“Push them too far, and they will flip over from a desired state that helps us to a state that will self-amplify in the wrong direction, going from cooling and dampening to self-amplifying and warming.”

To stay under 1.5° C of warming and avoid crossing tipping points, we need to stay within the “global carbon budget” set by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), noted Rockström. But we’ve already used up over 90 percent of that budget.

“What remains for us is only 200 billion tons of carbon dioxide that we can continue emitting to have a 50 percent chance of holding 1.5,” he said.

“We emit today 40 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year, giving us five years at current rates of emission before we’ve consumed the budget. We are seriously running out of time.”

The solution: “Bend the curve of emissions immediately and follow a path where we reduce emissions by at least 7 percent per year for a safe landing and a net zero world economy by 2050.”

Even then, we’ll inevitably face at least 30 to 40 years of overshoot before we come back to the 1.5° C limit.

“We must now be prepared for a very likely breaching of the 1.5º C planetary boundary on climate somewhere between 2030 and 2035,” cautioned Rockström.

The only solution: a rapid transition away from fossil fuels and toward sustainable food systems, regenerating forests, and more.

“I know that is very daunting,” said Rockström, “but what choice do we have when on the line is the future of our children on planet Earth?”

4. A planet-healthy diet is also healthy for you.

Worldwide, the food system accounts for roughly 25 percent of man-made greenhouse gas emissions.

“By far, the biggest single offender is the production of red meat, and especially beef,” says Walter Willett, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

Why? “The conversion of feed into edible flesh for humans is extremely inefficient, especially when we’re feeding grain to cattle,” explains Willett.

“And the vast majority of cattle, whether they’re for dairy production or beef production, are fed grain during much of their life cycle.”

Then there’s methane, a potent greenhouse gas.

“It’s produced in the forestomach of cattle as part of their digestion,” says Willett.

And the damage done by food is growing.

“Worldwide, many people want to eat more meat and more dairy foods as incomes go up,” notes Willett.

“That increased demand is driving deforestation as we chop down trees to grow food for cattle or allow them to graze.”

In fact, along with fires and droughts, deforestation is turning the Amazon from a carbon sink into a carbon emitter.

“We’re losing the trees, which may be the most important resource for capturing carbon,” explains Willett.

“And by plowing up the soil, we’re releasing methane that had been stored there. So it’s a double whammy.”

In 2019, Willett and the University of Potsdam’s Johan Rockström co-chaired the EAT-Lancet Commission, which set the parameters of a healthy, sustainable diet that could feed 10 billion people by 2050.

“We ended up with a diet that fits pretty closely with a traditional Mediterranean diet,” says Willett.

“It’s not a vegan diet; it’s an omnivore diet. It allows about one 3-to-4 ounce serving of red meat a week. Or, if you like big steaks, you could have a celebration once a month with a 12-ounce steak.”

The diet has room for one daily serving of dairy, but most protein would come from plants like beans, nuts, and soy foods.

“And this would be on a base of plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains,” says Willett.

“But there’s not much wiggle room,” he adds. “If the world went to two servings of dairy a day, or a bit more red meat, it wouldn’t fit within the EAT-Lancet’s estimates of what we can produce sustainably.”

Since then, his team has created a score to rate how closely a person’s diet comes to what they called a Planetary Health Diet. And they’ve tracked its links to health in some 200,000 nurses and other health professionals over roughly 30 years.

“Those who had the best adherence to the Planetary Health Diet had a lower risk of dying due not just to heart disease, but to cancer, neurodegenerative disease like dementia, and respiratory disease like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,” says Willett. “They also had a lower risk of heart attacks and strokes.”

Which foods mattered most?

People who consumed more whole grains, fruits, poultry, nuts, soy foods, and added unsaturated fats had a lower risk of dying, while those who ate more potatoes, red or processed meats, eggs, added saturated fats, added sugars, and sugar from fruit juices had a higher risk.

“We estimated that the diets of people with the highest scores accounted for about 30 percent fewer greenhouse gas emissions and about 50 percent less land use than those of people with the lowest scores, because they were eating foods directly, rather than running them through animals,” says Willett.

It’s the least we can do.

“Climate change is happening even though one might pretend that it’s not,” says Willett. “We can see the fires and floods and the heat that’s making many parts of the world not livable.”

“The consequences are going to be even worse 10 years from now, but it will be tragic for much of the world’s population by the end of the century, when our children and grandchildren will be alive. Once we’ve reached the tipping points, we can’t put the genie back in the bottle.”

Topics

More on sustainability

Planetary health diet: Good for you and the Earth

Sustainability

How to eat a flexitarian 'planetary health diet'

Healthy Eating

The Farm Bill: An opportunity to strengthen nutrition equity

Advocacy

A tale of two agendas: Trump’s contradictory approach toward small farmers

Advocacy

By Ben Feldman

Which fish are healthy and sustainable? It's complicated

Food Safety