How the food industry secretly influences what we buy

Want to know not just what’s in your food, but why? Marion Nestle’s new book, What to Eat Now: The Indispensable Guide to Good Food, How to Find It, and Why It Matters, tours the supermarket, from the meat, fish, dairy, eggs, and produce sections to the ultra-processed foods in the center aisles. If you’re confused about food, it’s for good reason, she says. You’re supposed to be confused. Here’s a glimpse into what shapes our food shopping.

Marion Nestle on food industry secrets

Marion Nestle is the Paulette Goddard Professor of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health, Emerita, at New York University and the author of 17 books, including Food Politics and Safe Food. She spoke with Nutrition Action’s Bonnie Liebman.

Why does the food industry try to influence what we buy?

MN: They want to sell as much food as possible at as high a price as possible to as many people as possible. If they don’t, their stockholders get upset and their stock prices go down.

They behave like any other corporation in our investment system. Food companies aren’t public health agencies. Once you understand that, you can better understand what you’re confronted with when you go into a supermarket.

Hasn’t that always been true?

MN: It’s gotten worse. In the 1980s, there was an enormous increase in food production, enough so that the calories in the food supply went up to 4,000 per person per day—that includes men, women, babies. Most people need only half that.

And then, because of the shareholder value movement, which came into its own in the 1980s, publicly traded companies were expected to not only consistently make a profit, but to grow their profit. They have to report growth to Wall Street every 90 days, which ramps up the pressure on them.

Did those changes affect more than just the food industry?

MN: Yes. This system has induced many publicly traded companies to treat workers poorly, produce profitable but unhealthful products, extract from and pollute the environment, lobby against regulation, and foist the health, social, and environmental costs of their practices on taxpayers.

How did the food industry respond?

MN: They put food everywhere. Foods and beverages are now more likely to be sold at places like gas stations, drugstores, and stores selling household items, like Walmart, Target, and Costco. My favorite example is bookstores. If you’re old enough, you can remember when bookstores wouldn’t let anybody with food anywhere near the books. Now bookstores sell their own food.

And aren’t portions much larger?

MN: Yes. I remember when muffins, which used to have 200 calories, suddenly had 800 calories, when bagels went from what we would now call mini-bagels to the giants they are today, and when 7-Eleven added a 64-ounce Double Gulp soda to its lineup.

Many restaurant portions are so big they could feed four people. I think larger portions are enough to explain the obesity epidemic.

How has the supermarket industry changed?

MN: It’s gotten more consolidated. The biggest four companies—Walmart, Kroger, Costco, and Albertsons—control half or more of all food sales. Kroger and Albertsons each owns roughly 15 smaller chains. Walmart alone controls a quarter of the market. That’s huge.

The bigger the chain, the more power it has to set wages and prices and exercise political power through campaign contributions and lobbying.

And we subsidize the wages of some of their employees?

MN: Yes. Stores like Kroger don’t pay some of their workers enough to live on, so many are on SNAP—the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program—which used to be called food stamps. So taxpayers are subsidizing the employees’ food purchases.

In 2020, a typical Kroger employee earned $24,617. Meanwhile, Kroger’s CEO earned more than $20 million.

Why does the book focus on supermarkets?

MN: I use supermarkets as an organizing device, but the same issues apply anywhere food is sold. How is it positioned? How is it priced? What does the packaging look like? What messages does it transmit?

The industry studies every bit of that as if it were a bible. They know which foods bring people into the store, which foods people look at, which foods go with other foods. They know exactly what pushes consumers’ buttons and makes them buy.

Like what?

MN: The more products you look at, the more products you buy. So stores are set up to make you do as much walking as possible, so you’re exposed to as many products as possible and you’re in the store as long as possible.

That’s why the milk is always on the wall that’s farthest from the entrance. That’s not an accident. Yes, the milk has to be against a wall so it’s easier to refrigerate, but it’s almost always on a far wall.

What else do stores do?

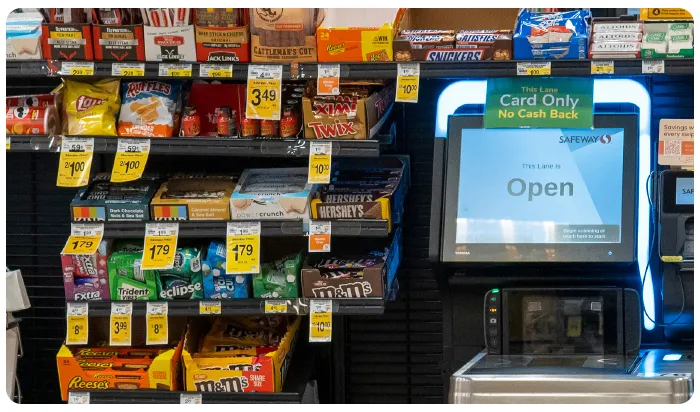

MN: They want impulse buys. So they make the most profitable products the most visible. They’re at the cash registers, the ends of aisles, or 60 inches above the floor—adult eye level—in the aisles. Companies pay slotting fees to put their products in those places.

Even the electronic self-checkout counters have products placed nearby, so at the last minute you’ll grab them and toss them into your basket.

And they want you to see some products again and again?

MN: Yes. That’s why drinks are not just in the drink aisles, but at the ends of aisles, at the entrance to the store, near the checkout. You can’t go through a supermarket without running into drinks everywhere.

What other foods are highly profitable?

MN: Ultra-processed foods. They’re relatively inexpensive, they’re attractively and conveniently packaged, and they’re backed by huge advertising budgets.

Why are they so profitable?

MN: Their ingredients can be purchased by food manufacturers when they’re at their cheapest. And most have an enormous shelf life. Many breakfast cereals, for example, can sit on the shelf for a year or longer.

Sellers of processed foods say they are just giving you what you want: easy-to-eat foods requiring no preparation, tasting better than anything you could make yourself, and guaranteed not to get moldy or spoil.

So what’s the problem?

MN: Many are deliberately designed to be irresistibly delicious, so that once you have a bag of them in front of you, you can’t stop eating them. And they’re often laden with sugar, salt, and calories or with additives.

Yes, there are a few healthier exceptions, of course, like some commercial whole wheat bread and flavored yogurt. But if you get your calories from ultra-processed foods, you’re not getting them from healthier foods that you have to cook.

Or from fresh fruits or vegetables that might spoil?

MN: Yes. And the food industry has normalized these foods so that many people get most of their calories from ultra-processed foods and snacks.

I would argue that it’s possible to eat healthfully in any supermarket in America. There’s a much greater variety of fruits and vegetables now in supermarkets everywhere I go. But you have to have the money, you have to know how to cook, and you need the time and energy to do it.

And food prices have gone up?

MN: That was one of the big shockers since I wrote the first edition of What to Eat in 2006. The prices we cited then have doubled.

Much of the increase happened since 2019, when supply-chain problems during the Covid pandemic led supermarkets to raise prices. But the stores have kept prices high, greatly increasing their profits.

They used those record profits to buy back stock and raise executive compensation rather than reduce prices for consumers or improve wages or working conditions for their employees.

Have prices risen more for fruits and vegetables?

MN: Yes. To anyone on a budget, fruits and vegetables appear expensive. And they are expensive relative to other foods. The price of fruits and vegetables has gone up higher than the average for all foods, and much higher than the price of ultra-processed foods.

And it’s hard to buy produce in low-income neighborhoods that have no supermarkets.

MN: Right. Supermarket chains avoid low-income areas. In general, they prefer to locate within a half-mile radius of a very large number of people who make $100,000 a year or more.

Switching gears, how does the food industry shift food safety burdens onto consumers?

MN: Chicken is frequently loaded with toxic Salmonella, but from the industry’s standpoint, it doesn’t matter because you’re going to cook it. And if you’re sloppy in your kitchen, it’s your fault, not theirs.

Other countries have made more progress reducing Salmonella because they insist that the producers take responsibility for it.

And it’s not just chicken?

MN: No. Fresh eggs carry the required safe-handling instructions: “To prevent illness from bacteria, keep eggs refrigerated, cook eggs until yolks are firm, and cook foods containing eggs thoroughly.” But you need a magnifying glass to read it.

And we shouldn’t have to run our kitchens like biohazard facilities.

Can’t vegetables and fruit also be contaminated?

MN: Yes, because they may be grown next to confined animal feeding operations that discharge a lot of waste into the local water supply and land.

The FDA calls them “non-sterile environments.” It’s a wonderful euphemism, but we’re talking about toxic bacteria from animal manure contaminating vegetables or fruit.

The book lists ‘what ifs’ that would fix our food system. What are some examples?

MN: What if more of our farmland were used to grow fruits and vegetables instead of the corn and soybeans that are used as feed for animals and fuel for automobiles? Maybe then, more people could afford to eat them.

What if supermarkets stopped taking slotting fees and devoted prime real estate to the healthiest products? What if the stores put packs of fruits and vegetables at cash registers? What if they insisted that their suppliers use sustainable production methods?

What if everyone in the food system paid workers fairly and treated them decently? What if they respected animal welfare? What if fast-food companies sold salads at a lower price than hamburgers?

Wow. We have such a long way to go. What’s the best diet advice in the meantime?

MN: The same diet is appropriate for preventing practically every chronic disease. I love Michael Pollan’s formulation: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.”

That takes care of it, for human health and for the planet, because the healthiest diet for people also creates the lowest carbon emissions.

I’m an omnivore, but I don’t eat a lot of meat. Most people would be better off if they replaced a lot of meat with vegetables. Unfortunately, the entire system is designed to make a very different diet the default.

Support CSPI today

As a nonprofit organization that takes no donations from industry or government, CSPI relies on the support of donors to continue our work in securing a safe, nutritious, and transparent food system. Every donation—no matter how small—helps CSPI continue improving food access, removing harmful additives, strengthening food safety, conducting and reviewing research, and reforming food labeling.

Please support CSPI today, and consider contributing monthly. Thank you.

More on healthy eating

Cozy bowls and power salads for peak fall and winter flavor

Healthy Eating

By M.M. Bailey

How food assistance programs can feed families and nourish their dignity

Advocacy

Creative main dish recipes for a no-turkey Thanksgiving

Healthy Eating

By M.M. Bailey

The benefits of healthy school meals for all

Healthy Kids

What’s in season: March produce guide

Healthy Eating

By M.M. Bailey