Alzheimer’s: What may prevent, diagnose, or treat the disease

Eslie Rodriguez - stock.adobe.com.

Remember when your memory was better? “Cognitive aging” is normal. Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias are not. Here’s what’s in the pipeline to diagnose, prevent, and treat those problems...and what you can do now.

Does lithium orotate protect the brain?

“New hope for Alzheimer’s: lithium supplement reverses memory loss in mice,” ran the August headline in Nature.

Though most of the study was done in mice, the researchers first tested the levels of 27 metals in the preserved brains and blood of deceased people who had had Alzheimer’s, mild cognitive impairment, or normal cognition.

One metal stood out.

“They found a deficiency of lithium in people with mild cognitive impairment, and the deficiency was even worse in those with Alzheimer’s disease,” explains Ashley Bush, professor of neuroscience and psychiatry at The Florey Neuroscience Institute of the University of Melbourne in Australia. He wrote the editorial accompanying the study.

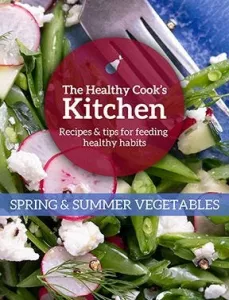

“And what lithium was there was trapped in amyloid plaques,” adds Bush, an expert on metals and neurodegenerative brain diseases. (Amyloid plaques and tau tangles are the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s.)

Do plaques starve the brain of the lithium that it needs to function?

To find out, the researchers used “a mouse model that has been engineered to generate amyloid plaques,” notes Bush.

Sure enough, when those mice were fed a lithium-deficient diet, they accumulated more amyloid and tau tangles and were worse at tasks like recalling the location of a platform in a water maze.

What’s more, “microglia—cells that normally act as the brain’s local immune defense—became pro-inflammatory and had an impaired ability to clear amyloid,” says Bush.

In contrast, “treatment with lithium reversed all the pathology that was seen in the mouse model. Lithium improved amyloid and tangles, improved synapses, reduced signs of inflammation, and the animals’ cognition improved.”

The researchers used lithium orotate, not lithium carbonate, a drug that’s prescribed to treat bipolar disorder. Both are what scientists call “salts.” “Lithium is the positive part of the salt, and the orotate or carbonate is the negative part,” explains Bush.

“The researchers reasoned that salts that bind the positive and negative parts more strongly together are less likely to break apart and allow lithium to be trapped by amyloid.”

“They studied 16 salts, and lithium orotate was the least likely to separate. And it was indeed superior to lithium carbonate in treating the mice.”

What’s the next step?

“This study raises the question: Is Alzheimer’s due to a lithium deficiency?” says Bush. “That’s not known.”

More importantly, “this study should encourage clinical trials testing lithium orotate in people with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s. That’s what’s needed before we can make any recommendations.”

One upside: “The doses of lithium orotate used in the mice were much lower than a customary dose of lithium carbonate,” says Bush. “A lower dose of lithium would be good because lithium has toxicity problems. Blood levels can’t go beyond a certain level, or you can get damage to kidneys, the thyroid, and other problems.”

What about the lithium orotate supplements you can buy online?

“The doses that are typically sold online—5 to 10 milligrams a day—are too low to cause toxicity problems, so they seem safe to take,” says Bush.

“But at this stage, there’s no evidence in humans that they’re beneficial, and we don’t know what dose to use.”

The bottom line: Research on lithium is just beginning. Stay tuned.

2. Anti-amyloid treatments don’t improve memory

The FDA has approved two blood infusions—lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab (Kisunla)—to reduce amyloid deposits in the brain. But many physicians may not convey the drugs’ limitations to their patients.

“They say, ‘The drugs work,’ and the truth is, the drugs do slow the progression of the disease,” says David Knopman, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic. “But the drugs do not make people better. And they do not stop the disease. It’s only a slowing.”

“I don’t think that most docs really understand that efficacy data. They just take it at face value that Eisai—which sells lecanemab—says you get a 27 percent benefit. But that’s 27 percent less decline, not a 27 percent improvement.”

And a 27 percent slowing is modest. Patients or their families may not even notice the difference.

Another source of confusion: How long patients need to take the drugs.

With lecanemab, you have to get infusions every two weeks for 18 months and then continue monthly—or weekly using an injection pen at home—indefinitely with a maintenance dose, says Eisai, because plaque keeps accumulating.

In contrast, donanemab is infused only monthly and for only 18 months.

“The fact is that we really don’t know what needs to be done after 18 months,” says Knopman.

That’s how long the trials for both drugs lasted. Once they ended, “we had no control group,” he notes, so you can’t compare people who got the drugs to those who didn’t.

Knopman recently wrote an article with Eli Lilly, which sells donanemab. (Knopman has no current ties to Lilly, Eisai, or other relevant companies.)

“With donanemab, if you don’t achieve close to full clearance of amyloid by between week 52 and 76, you’ll get negligible benefit from the treatment,” he explains.

“And if you do get complete clearance, it takes 10 to 13 years for brain amyloid to re-accumulate.”

That’s why a “maintenance dose” of lecanemab may not make sense.

What’s more, adds Knopman, “after 76 weeks of biweekly infusions, people are tired.”

(Roughly one out of five people taking lecanemab or donanemab get swelling or small hemorrhages in the brain. These “ARIA” can be serious, but they typically occur early and cause no symptoms.)

Still, it’s not easy to stop treatment. “In the absence of real data, it’s a difficult decision for physicians and families,” says Knopman.

On the bright side, more treatments are on the way.

“First, Novo Nordisk has a trial testing Wegovy that should report results later this fall,” notes Knopman, referring to semaglutide, the GLP-1 weight-loss drug that’s also sold as Ozempic for people with type 2 diabetes. (One reason to test Ozempic: In clinical trials, people with type 2 diabetes who were randomly assigned to take GLP-1 drugs to lower the risk of cardiovascular disease also had a lower risk of dementia.)

“Second, there’s a new anti-tau agent that’s an ASO—an antisense oligonucleotide,” says Knopman.

The agent binds to the mRNA that produces tau proteins in neurons. Once bound, the agent—called MAPTRX—recruits an enzyme that destroys that mRNA, so the neurons make less tau. “Those results are expected next summer,” notes Knopman, though they won’t be definitive because it’s only a “phase 2” trial.

A third treatment won’t have results for years. “It’s a drug called trontinemab, which has what’s called a brain shuttle technology,” explains Knopman.

“That appears to greatly increase the transfer of an anti-amyloid antibody into the brain. The early data appears to suggest that the drug may work better for removal of amyloid and be safer than lecanemab and donanemab.”

“Hopefully, these new classes of treatments in the pipeline will add to the toolbox to treat Alzheimer’s.”

3. A blood test alone can’t diagnose Alzheimer’s

In May, the FDA approved the first “device that tests blood to aid in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease.”

The Lumipulse test measures the blood levels of two proteins: p-tau217 and beta-amyloid 1-42.

The FDA is reviewing similar tests, but LabCorp, Quest Diagnostics, and other labs now also offer their own “lab-developed tests” for p-tau217 that haven’t been approved by the FDA.

“Blood tests for p-tau217 are being widely used,” says Knopman. Is he worried that doctors will use only a blood test to diagnose Alzheimer’s?

“I’m terrified of it. I don’t have the exact numbers, but Mayo alone is running a staggering number of samples a week.”

Yet a blood test is not definitive. “You couldn’t be more conceptually misled than to think that you can use a blood test alone to diagnose mild cognitive impairment or dementia,” says Knopman. “Those are clinical diagnoses.”

“People might think, ‘My plasma p-tau217 says I’m in the Alzheimer’s range. Oh, I must have dementia,’ even though their neuropsych testing is blazingly normal. It’s scary.”

Blood tests can’t leapfrog over neuropsychological tests, says Knopman. Why?

For starters, the lab results mistakenly detect tau in about 20 percent of people with no symptoms. “That’s good enough for screening but certainly not good enough as a stand-alone diagnostic test,” he notes.

And roughly 20 percent of people get results that fall into a neither-positive-nor-negative “gray area.”

Another reason not to rely solely on a blood test: Neuropsychology test results might be borderline.

“The distinction between cognitively normal and mild cognitive impairment, or MCI, has some wobble to it, even in the best of hands,” Knopman points out.

“So you might end up treating people who are ultimately normal or who, even if they have elevated brain amyloid in PET scans, are still years from becoming symptomatic.”

We don’t know the “lag time”—that is, how soon symptoms begin after blood levels change. In fact, an estimated 24 percent of older people with elevated amyloid are cognitively normal.

What’s more, “most people still use the word Alzheimer’s to mean all dementia,” says Knopman. “But not all cognitive impairment and dementia is plaque-and-tangle disease.”

“Maybe a third of those patients have pure Alzheimer’s. Especially as they get older, many will also have cerebrovascular disease that contributes to their cognitive impairment.”

“Or they might have Lewy body dementia or a combination of those disorders and no Alzheimer’s pathology at all. It takes expertise to identify those conditions.”

Another group who shouldn’t get anti-amyloid treatment: People whose memory loss is too advanced.

“It’s quite clear that people who don’t just have mild dementia but are trending into the moderate range will not benefit from treatment,” says Knopman.

4. A healthy lifestyle helps

The FINGER (Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability) trial got there first.

“In 2015, the Finns reported that a large, multidomain lifestyle intervention in at-risk older adults could improve cognition,” says Laura Baker, professor of gerontology and geriatrics at Wake Forest University School of Medicine and Advocate Health.

But would it work in the US? We differ in many ways.

“In Finland, people rarely miss their annual, or sometimes twice-a-year, check-up,” notes Baker. “Here, we had people who had not seen a doctor for five years.”

“And in Finland, there are bicycles everywhere. Here, the few people on bikes are really fit, not typical Americans. We eat a lot of processed foods. They don’t.”

So in 2016, the Alzheimer’s Association invited Baker and others to start planning the US POINTER trial.

“We wanted people who were cognitively normal but had risks for decline like family history or mild cardiovascular disease,” says Baker.

The 2,111 participants were randomly assigned to either a “structured” or a “self-guided” group.

The structured intervention included 38 team meetings, exercise training at a gym, encouragement to eat a MIND diet, cognitive challenges, social engagement, and a biannual review of their blood pressure, cholesterol, and hemoglobin A1c (blood sugar levels).

The self-guided group got healthy lifestyle advice and $75 gift cards at six team meetings, plus annual clinic visits to check their blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol.

After two years, “both groups improved, but the structured group improved significantly more,” says Baker. “Their scores were comparable to adults who were one to two years younger.”

That’s based on a “global cognitive score.” Of its three components, executive function (planning, multitasking, problem solving) improved more in the structured group. Processing speed and episodic memory didn’t.

“We’re now analyzing other measures like brain imaging, sleep, and vascular health,” says Baker.

One advantage of a “multidomain” program: “The intervention can be tailored to the person,” she points out.

“For example, some adults have physical limitations and cannot safely exercise at moderate intensity. Others may have difficulty adhering to the MIND diet due to reduced access to healthy foods.”

If so, they can make other changes. The same goes for cognitive challenges.

“We asked people to complete BrainHQ online training for about 20 minutes three times per week,” says Baker. “Some people loved it, others did not. We also asked them to go out and meet people, learn a language, go to a library, watch a documentary, get out of their comfort zone.”

The trial tried to make it easy for people to eat a healthier diet.

“The MIND diet is a Mediterranean-like diet but low in salt,” says Baker. “The participants were asked to keep track of some foods: like did they get four servings a week of dark leafy greens, or three servings a week of blueberries, or how much sugar did they eat?”

Her take-home message: “Lifestyle does matter for brain health. By moving more, eating more fruits and vegetables, staying connected to people, and taking responsibility for your blood pressure, blood sugar, and cholesterol, you can protect your brain health.”

Do the DASH

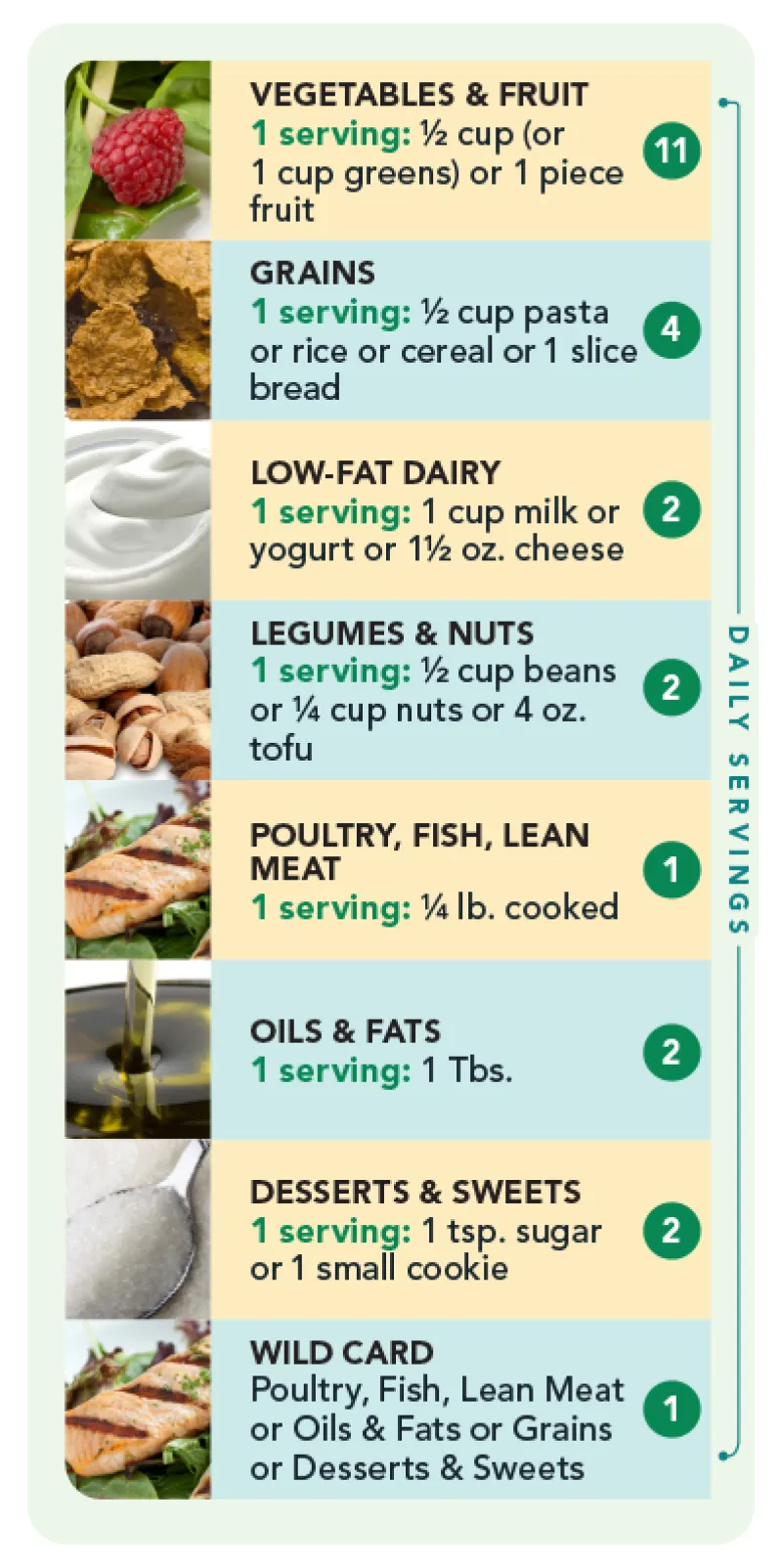

A MIND diet is like a DASH diet, except it’s richer in blueberries, nuts, extra-virgin olive oil, leafy greens, and fish. And it should help protect the brain by keeping a lid on blood pressure. Here’s a 2,100-calorie version.

To protect your brain

Here’s what else may preserve your memory.

- Aim for a systolic blood pressure below 120.

- Keep a lid on blood sugar and LDL (“bad”) cholesterol with diet or medication.

- Don’t smoke.

- Aim for a healthy weight.

- Exercise for at least 150 minutes a week.

- Stay mentally and socially active.

- Get 7 to 9 hours of sleep.

- Consider taking a daily multivitamin. That slowed cognitive decline modestly in an earlier clinical trial. At a minimum, you’ll get vitamins B-12 and D that you may not get from food.

- Don’t bother taking ginkgo, omega-3 fats, or Prevagen.

Support CSPI today

As a nonprofit organization that takes no donations from industry or government, CSPI relies on the support of donors to continue our work in securing a safe, nutritious, and transparent food system. Every donation—no matter how small—helps CSPI continue improving food access, removing harmful additives, strengthening food safety, conducting and reviewing research, and reforming food labeling.

Please support CSPI today, and consider contributing monthly. Thank you.